Alexander (“Sanny”) Sloan is best known as the former Labour MP for South Ayrshire, a position he held following a 1939 by-election until his death in November 1945. Below we feature a recollection of him, written in 2014, by his great-granddaughter, Esther Davies. This article has been revised recently to become part of a much longer account of his life and work, and is now one of the Society’s occasional publications.

Recently, someone suggested that I write out what I can remember of family stories, and particularly those about my “Granta” Sloan, who died when I was three. I always knew that my great-grandfather “Sanny” (Alexander) was a socialist MP, who represented South Ayrshire from 1939 to 1945, and had been involved all his life in trade unions and local government. I also knew that he had experienced great poverty and injustice, and the dreadful effects of war. He fought against these evils on behalf of ordinary people, for individual rights for workers, for better employment conditions, better housing, better education and training, freedom for the colonies and for lots of things now accepted as reasonable but then seen as radical. Further, I knew that old men would weep at the mention of his name and recount what he had done for them.

Early Years

Alexander Sloan was born on 2nd November 1879. His parents were John Sloan (1853-1923) and Esther McCloy (1854-1921), who had married in Dalry in Ayrshire on 27th December 1872. The couple had twelve children – two daughters and ten sons. The first three were born in Dalry, and the remainder after the family had moved to Rankinston. Of the twelve children, three died in infancy or early adult life. Margaret, the elder daughter, died of tubercular meningitis, aged ten, while James died of tubular nephritis, aged thirty. Esther’s penultimate pregnancy produced twins, one of whom died within three weeks. Their last child, Robert Thomson Sloan, was named after him.

Sanny’s father, John Sloan, was an ironstone miner, and when the pit at Dalry closed, he and his family moved to Rankinston, in the hills of Coylton parish, where new pits were being opened up. They walked the forty or so miles from Dalry to Rankinston, with any large possessions being sent on the mineral train. Mining families lived in the appalling housing supplied by the mining company – miners’ rows where the houses were tiny, one or two rooms with earth floors under the set-in beds. At Rankinston the new rows of houses were built to the same plan as had existed at Dalry. The Sloans, and many of their neighbours and colleagues, moved into the “same” house in the “same” street as they had occupied at Dalry. These Rankinston houses had no wash-houses; water came from a spring on the hillside above the village, and was piped to stand-pipes in the streets, whence it had to be carried home. The earth closets were shared, with one to every five families. This was a better ratio than had prevailed at Dalry. At Rankinston, too, the closets were better built, had doors, were easier to keep clean, and so were more hygienic. The rents for the houses were high, and the company also owned the village shop (using the notorious “truck” system), the pub, the school, and provided a company doctor. Employees were obliged to use these facilities and each miner paid a penny a week for the services of the doctor. The miners lived in abject poverty within a tightly controlled community. Despite having lots of children, census records show that the Sloans also had an elderly lodger to help make ends meet, and this was a common occurrence in Rankinston, and in other mining villages.

It is surprising that so many of the children survived into adulthood. The boys left school at twelve, and followed their father into the pits. Esther, the surviving daughter, found work on a farm when she left school and later married a miner. The hard life was to some degree alleviated by the closeness of the families. Esther began her married life in her parents’ house. Next door to the Sloans lived Esther McCloy’s younger brother – a widower whose wife had died in childbirth – with their three small children, and with his mother as housekeeper.

Work and Politics

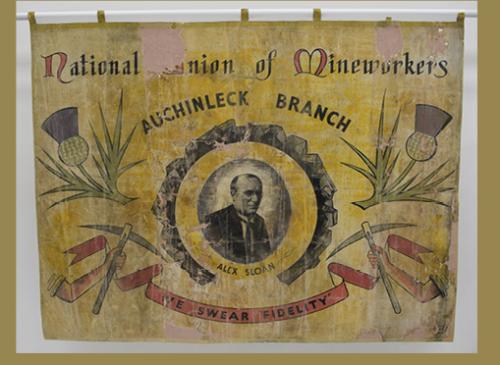

Alexander (Sanny) was John and Esther’s fourth child (and second son) and was the first to be born after the family moved to Rankinston, and he became strongly associated with – and committed to – the village throughout his life. Like his brothers he began work in the mines, when he was twelve, but he was injured in a pit accident and lost the sight in one eye. He returned to work, but in a lighter job. He became very involved in the struggle for the rights of ordinary people through fighting the injustices which he had first experienced himself. He was just as concerned about injustice to others. He wanted equal opportunity for all. He was passionate about education and was elected to Coylton School Board in 1900. In 1919 he also became a member of Ayrshire County Council, on which he served for 25 years, and he was a prominent and active member on the education committee, and also chaired the housing committee. For nine years he was the secretary of the Scottish Miners’ Federation, and he was a Labour MP from 1939 to 1945, when he died. A man of wide interests, he also argued for colonial independence, and better conditions for serving soldiers.

Family Life

He married Agnes Sloan, no relation, but who also came originally from Dalry. She had left school at seven, and worked in a mill, where she had to stand on a box to reach her machine. One of seven children, only two of whom reached old age, she was a bright, go-getting woman. Once she had settled in Rankinston she was able to purchase a piece of land, just below the village, from a local farm. Here she built a grocery store, also selling general goods and linens, and this soon developed into a profitable business. For unknown reasons, this act of defiance was ignored by the mining company. When a new doctor came to the district, a Dr Macrae, whose main business was amongst the local farming community, Agnes felt that he was a better doctor than the company man, so she went to him. When, again, no sanction was imposed, others began to follow suit. This was frank disobedience, and the company decided enough was enough. Alexander was sacked and blacklisted and he, his pregnant wife and children, Rab and Esther, were evicted from their tied company house. For a while they lived in a farm barn, while they built a house alongside the shop, using a loan guaranteed by Dr Macrae. The income from the shop allowed them to keep going. A final child, John, was born while they were living in the barn.

The building of the house, known as Kerse Cottage, was not without its problems. The Sloans wanted to install running water, but the company initially refused them permission to take a supply from the village spring. However, Alexander found that the pipe ran through their property, and so water was installed. Shortly after, someone mentioned to a company manager how fortunate the Sloans were to have hot and cold running water. The response was to cut off water from the whole village, including the school. Alexander found that there was a by-law which stated that all schools must have running water, so he took the company to court and, as a result, after three days without, water was restored to the 700 people of Rankinston.

Activism and Commitment

Because of his militant activism, and also because of his poor eyesight, Sanny had problems finding work. For a while he sold Singer sewing machines; he spent some time as an insurance salesman, and also worked for the miners’ union as a checkweighman, later becoming a miners’ agent. In 1921 he became involved in a bitter industrial dispute. The coalminers were on strike against massive pay cuts. A group of volunteers was endeavouring to keep the Houldsworth Colliery, at Polnessan, in good order by pumping out the water. A group of miners called at Sloan’s house about one o’clock in the morning, wishing him to join them in stopping this. He agreed to do so, and the group of seventeen miners walked to the Houldsworth pit, arriving about half past two. With four others, Sloan went into the office to confront the dozen or so volunteers. He advised them that there was a large crowd outside, and that for their own safety, they should put out their fires and close the pit. The volunteers co-operated, and went home, but the five men, who also included Sloan’s brother Henry and son, Rab, were charged with "mobbing" and rioting, and held in Barlinnie Prison in Glasgow. This charge carried a maximum tariff of life imprisonment, but in a case held before the High Court, it was found that five was too small a number to constitute a “mob”. However, they were found guilty – with Sloan, seen as the ringleader, sentenced to three months imprisonment, and the other four jailed for six weeks.

Meanwhile, the shop thrived, but had to close during the 1926 General Strike, as all the stock had been exchanged for union promissory notes. During the strike, the soup kitchen for the village was established in the Sloan’s wash-house, but, later the same year, Agnes died, aged 47, from phlebitis. She was a remarkable woman in her own right; it is reported that she was in the habit of going to auctions to buy porcelain to sell in the shop and she also bought furniture to give to those who had none.

Alexander Sloan continued to be a powerful voice for the poor and the underdog. He often appeared in court in compensation cases, getting good results for union members who had been injured in the mines, despite a long history of courts declining to award compensation, even when safety measures were the clear responsibility of the mine-owners. Some thirty years after his death, a relative contacted the courts enquiring about any records concerning Sloan, only to be told by the receptionist that they had none. But she did ask if it was an enquiry about a compensation case, because she recognised his name.

However, Sanny’s greatest obsession was education. He had educated himself throughout his life. He was apparently a passionate speaker on the political stage, and a great Burns man, popular at Burns Suppers, and well read. It was not just about expecting public provision, which he wanted, it was also about personal commitment, and the following story illustrates this selfless commitment. Sanny’s grand-daughter, Agnes Davies, met a fellow-teacher on the bus. She asked Agnes where she came from, and when she replied Rankinston, asked if she knew any Sloans. Agnes said she was a Sloan on her mother’s side. It transpired that her grandfather had been asked for advice by a miner with several children, who could not afford to send his daughter to university. The fees could be paid by the Carnegie Trust, but he would not be able to afford the living expenses any longer. Sanny said he would send him money quarterly, and if the daughter became rich, she could pay him back, but if not, it was fine to forget it. The stranger on the bus was the daughter, now a teacher. None of the family knew of this act of generosity, which only came out thirty years later on the local Patna bus.

“Sanny" Sloan, the Miners’ MP – his life, times and family by Esther Davies is available to order from the SLHS website (£6.00 plus £2.00 p&p).