Writing in the late 1950s, Raymond Williams (then an adult education tutor) suggested that the culture of the working class since the Industrial Revolution had been 'primarily social' rather than 'individual', typically creating 'the collective democratic institution, whether in the trade unions, the co-operative movement or a political party'. 'When it is considered in context,' he concluded, 'it can be seen as a very remarkable creative achievement.'*

We highlight here some of the artwork – banners, paintings, prints – produced by the Scottish working class, through its democratic institutions, over its 250-year history, believing they offer another way of seeing its attempts to realise its own emancipation.

*Raymond Williams, Culture and Society (1958), p327

According to the historian of the friendly societies of England, these organisations first appeared, as an early example of collective self-help, in the late seventeenth century and, along with the trade unions and later co-operative movement, came to 'represent the ways in which those without political power sought to protect themselves in an increasingly industrialised society.'1

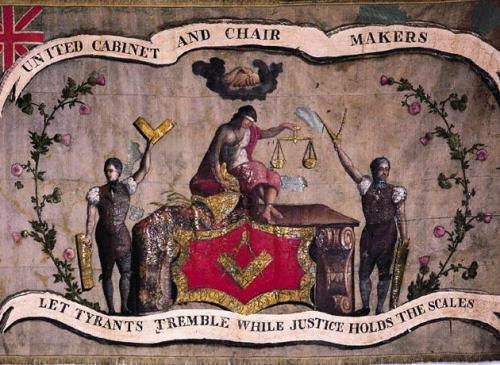

Little is known about the Scottish National Union of Cabinet and Chair Makers, a craft union which was flourishing in the early 1830s, but its banner, preserved in the Edinburgh City Museum collection, is one of the oldest surviving Scottish trade union banners.2

- P H J H Gosden, The Friendly Societies in England 1815-1875 (1961), p7

- Arthur Marsh & Victoria Ryan, Historical Directory of Trade Unions, Volume 3 (1987), p336

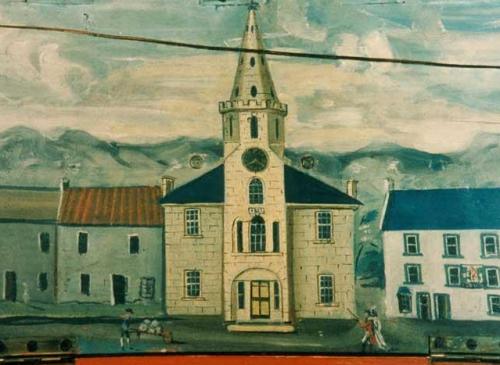

The Dairsie Political Association banner, from Fife, derives from one of the campaigns for political reform during the nineteenth century, presumably the extension of the franchise ahead of either the 1832 Reform Act, which gave the vote only to the middle classes, or the 1867 Reform Act, as a result of which some working men gained the vote.

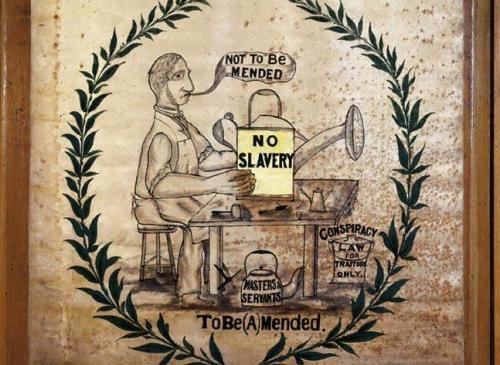

The Tinplate Union banner highlights a campaign, during the 1860s, around the law governing the 'master and servant' relationship, which criminalised workers for any breach of contract and which was keenly felt in Scotland. The campaign to reform the law was led by Alexander Campbell and George Newton of Glasgow Trades Council, along with Scottish miners' leader Alexander McDonald.1 The union, whose banner is shown, was probably the United Tin-plate Workers Protective Society. 2

- Henry Pelling, A History of British Trade Unionism (1963), p64

- Arthur Marsh & Victoria Ryan, Historical Directory of Trade Unions, Volume 2 (1984), p122

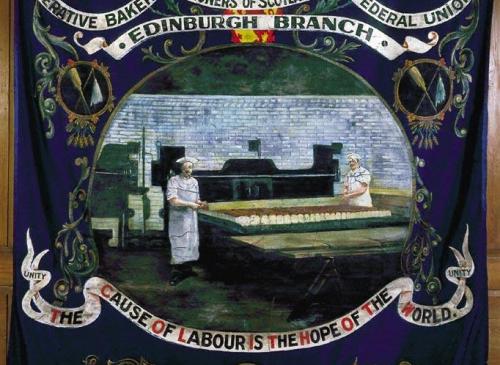

The Operative Bakers & Confectioners of Scotland had been formed by an amalgamation of smaller unions in 1888 and undertook a partially successful national strike in 1889 for a 55-hour week.1 After further amalgamations in the earlier twentieth century, the union merged with USDAW in the 1970s.2

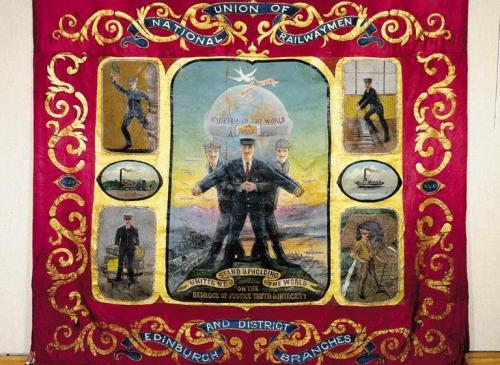

The National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) was formed in 1913 from an amalgamation of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, the United Pointsmen's and Signalmen's Society and the General Railway Workers Union.3 The NUR merged with the National Union of Seamen in 1990 to form the National Union of Rail, Maritime & Transport Workers (RMT).4

Both banners reflect the growing pride and self-confidence, as well as the higher national profile, of trade unions in the earlier twentieth century.

- W H Marwick, A Short History of Labour in Scotland (1967), p51

- William Richardson, A Union of Many Trades: a History of USDAW (1979), p34

- Philip S Bagwell, The Railwaymen (1963), ch XIII

- Sean Geoghegan & Brian Denny, Pulling Together (2009), p28

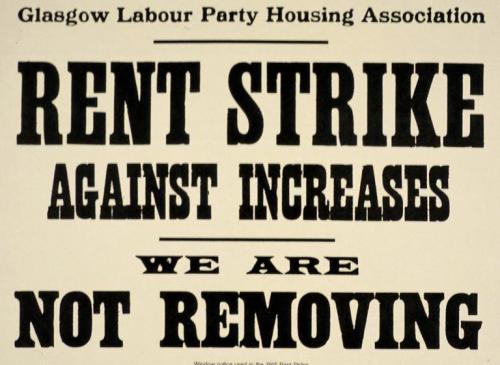

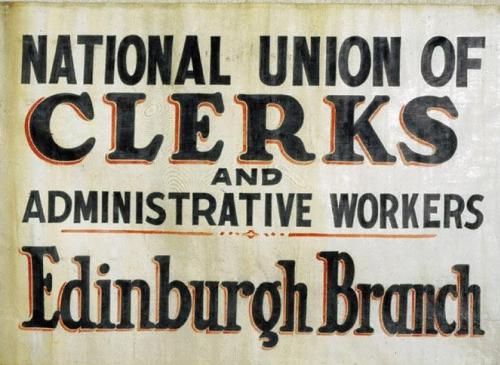

Bold typography shown to be effective both for political campaigning, as in the successful Glasgow Rent Strike led by Mary Barbour and others in 1915, and in union banners, as shown on the Edinburgh branch banner of the National Union of Clerks and Administrative Workers in 1920.

All images courtesy of SCRAN, a resource of Historic Environment Scotland, bringing together material from Scottish local authority and other collections.